Mar 31, 2022

Shifts in Yen Signal Japan ‘Lost Its Mojo’ as Supreme Safe Haven

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- What a difference eight years make for Japan’s currency.

“Yen Rises for Fifth Day Amid Ukraine Tension,” a Bloomberg News headline exclaimed in March 2014, when Russia was moving in on Crimea. The story noted, “Investors sought haven assets” amid intensifying geopolitical risks.

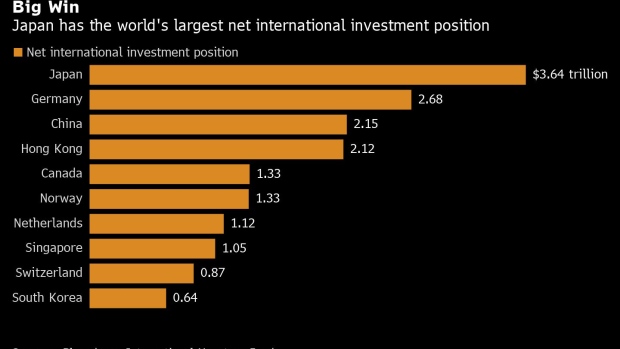

It was the kind of move seen time and again over the years -- a basic tenet of global markets was that when bad things happened, traders piled into the yen. It stemmed from Japan’s status as the world’s largest net creditor. Japan didn’t need anybody else’s money, and it had a whole lot of assets.

Japan is still the top creditor, but the yen isn’t behaving quite the same way any more. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, massive geopolitical shock and “risk-off” trigger for investors that it was, is hardly detectable on a dollar-yen chart. What does stand out is the yen’s big tumble in recent weeks, triggered by a widening gap in monetary policy.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda this week made clear he’s determined to keep his near-zero target for 10-year bond yields. That’s in the face of pressure for yields to shoot higher in response to the global selloff in government debt, triggered by the BOJ’s peers moving to tighten monetary policy.

Read More: Kuroda Puts Yields Before Yen With BOJ’s Credibility at Stake

By contrast, the Federal Reserve is preparing to boost its short-term policy rate as much as half a percentage point in May and unveil a runoff in its bond portfolio.

The divergent paths sent the yen to its weakest against the dollar in seven years in March. It’s down more than 5% since the start of 2022.

Compared with some other currencies, including the euro, the yen hasn’t fared quite as poorly. Even so, when measuring it against a basket of units of trading partners, its fading allure can clearly be seen:

The nation’s current-account surpluses have for some time now owed largely to cash flows from the stockpile of overseas assets, rather than to Japanese firms’ vaunted export prowess. Lately, Japan has even been running trade deficits, thanks to surging costs for energy imports; the gap widened to 1.03 trillion yen ($8.5 billion) in February, among the largest deficits on record.

“The yen’s failure to rise in a risk-off environment indicates the increasing influence of commodity prices and ensuing terms-of-trade shock,” Tohru Sasaki, head of Japan markets research at JPMorgan Chase & Co., wrote in a recent note. “The vicious cycle between a deteriorating trade balance and falling yen may have started.”

Wariness of exactly such an outcome may mean that Tokyo’s official tolerance for yen weakness only runs so far, said Alvin T. Tan, head of Asia FX strategy at Royal Bank of Canada.

A cheaper yen could also in time lead to bigger exports. Kiyoshi Ishigane, chief fund manager at Mitsubishi UFJ Kokusai Asset Management Co. in Tokyo, which oversees more than $172 billion, highlighted the potential for a trade turnaround in concluding that “the yen remains a haven asset.” He added, “Japan’s large surplus in its international investment position backs up the currency’s value.”

Others read underlying signs of concern.

Japan’s massive debt -- some 259% relative to the size of the economy last year, the highest among developed nations, according to the International Monetary Fund -- means that if yields ever do surge, the financing burden could quickly raise sustainability questions.

Another consideration: Japanese companies mounted record overseas acquisitions before the pandemic -- aiming to reduce dependence on a home market with a shrinking population -- and such flows could resume, causing sales of yen for foreign currencies.

Also of note is that in the current environment of high global inflation, Japan’s relative price stability ought to have some appeal. The core inflation rate was an annual 0.6% in February, against 6.4% in the U.S. Adjusted for consumer-price gains, Japan’s yields are higher than U.S. ones.

Increasing global interest in China’s bond market -- which saw record inflows before a recent retreat by foreign investors -- is another warning sign. A recent IMF paper illustrated how diversification of foreign-exchange reserves out of dollars hasn’t benefited the yen.

“This suggests that the doubts about Japan’s currency now run deeper: that it has lost its mojo as a safe-haven, ceding ground to alternatives,” said Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economic research at HSBC Holdings Plc. “Something more than monetary policy divergence might thus be at play.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.