Mar 5, 2024

Bank of Canada to hold as downside risks fade

, Bloomberg News

The time to start solving these big fiscal problems is now: Former BOC governor

The Bank of Canada is likely to hold interest rates steady for a fifth straight meeting, as dwindling recession risks allow policymakers more time to get a clearer read on inflation before they adjust borrowing costs.

Markets and economists widely expect policymakers led by Governor Tiff Macklem to hold the benchmark overnight rate steady at 5 per cent on Wednesday. Officials will probably maintain a neutral stance, reiterating that they still want more evidence that their campaign to rein in price pressures is working.

“There isn’t a strong argument for them to come out as especially dovish,” Doug Porter, chief economist with the Bank of Montreal, said in an interview. “They don’t really have to change their tune.”

In January, the bank explicitly dropped its hiking bias. Nothing in the economic data since then seems likely to compel Macklem to act or offer guidance about the timing of future rate cuts.

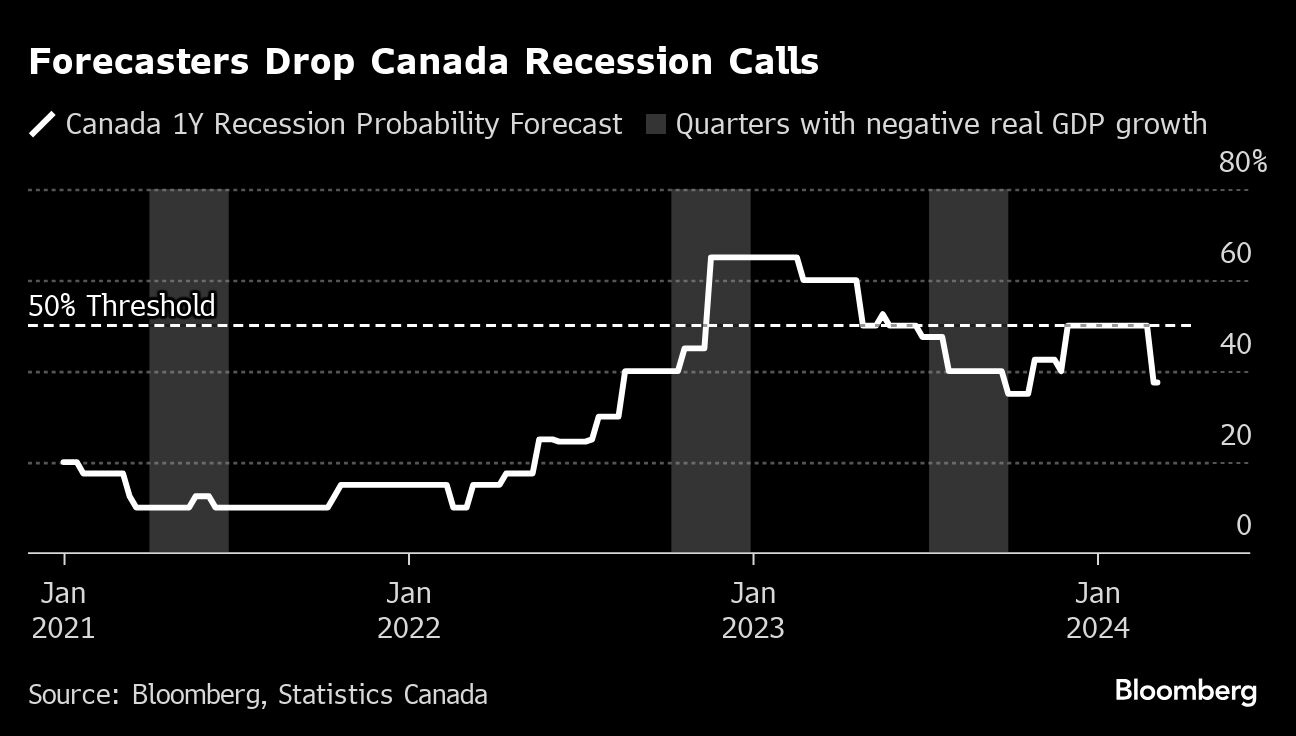

The economy is growing slowly, but it’s not rapidly worsening, expanding at a 1 per cent annualized pace at the end of last year. Recession calls among major lenders have faded, and a so-called soft landing is increasingly seen as the most likely scenario.

And while the country’s labor market is weaker than it was a year ago, the unemployment rate reversed course and fell to 5.7 per cent in January. Importantly, growth in the U.S., the country’s largest trading partner, is also proving stronger — pushing back bets on when the Federal Reserve will start cutting.

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg see the bank’s first cut happening in June, with subsequent easing bringing the policy rate to 3 per cent by the end of 2025. Traders in overnight swaps put the odds of a cut at about a third at the bank’s April meeting, with the first full 25-basis point cut priced in July.

“We expect the bank will want to hold its cards close to its chest until the April monetary policy report,” Avery Shenfeld, chief economist with Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, said by phone. “It’s too early for them to provide a lot of guidance on when lower rates might happen.”

The yearly change in the consumer price index decelerated to 2.9 per cent in January, just the second time in 34 months that price pressures have fallen below the 3 per cent cap of the bank’s target band. Still, core inflation has proved sticky, and officials have repeatedly said they won’t turn to a discussion of cuts until they’re satisfied they’re seeing sustained evidence of disinflation.

“The Bank of Canada needs to be confident that inflation’s coming back to target and they’re not exactly there yet,” Tiffany Wilding, an economist with Pacific Investment Management Co., said in an interview. “We’re going to be focused on how they’re characterizing inflation.”

This year, there’s more opportunity to hear from Macklem himself — each of the eight rate decisions is followed by a news conference with the governor and Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers. In the past, they would do only four post-decision news conferences in a year.

Macklem and Rogers may need to address mounting evidence that the country’s housing market has already started to pick up, as the promise of lower mortgage costs and looser financial conditions run up against a shortage of homes.

The bank probably won’t give an update on its plans to continue shrinking its balance sheet — Deputy Governor Toni Gravelle will deliver a speech on quantitative tightening later this month. Over half of economists surveyed by Bloomberg expect the bank to end quantitative tightening by the July meeting, sooner than officials had outlined last March.