Oct 13, 2020

Delta delays US$5B of jetliner deliveries in blow to Airbus

, Bloomberg News

Delta Air Lines Inc. is delaying US$5 billion in aircraft deliveries until after 2022, dealing a blow to Airbus SE as the U.S. carrier braces for years of weak travel demand.

The deferrals include about US$2 billion in planes that were scheduled to be handed over this year, Delta said in a statement Tuesday as it reported worse-than-expected quarterly results. The delays extend to a small number of CRJ regional jets made by Bombardier Inc., Delta said, without providing a comprehensive breakdown of all the planes affected.

The revamped delivery schedule will ease cash strains during the next two years as Delta shrinks its operations to contend with the coronavirus pandemic, which has caused an unprecedented collapse in commercial flying. Like other airlines, the Atlanta-based company has already slashed spending by parking planes, cutting flights and thinning its employee ranks in response to the crisis.

“This has less to do with the outlook for demand and more to do with our cash situation,” Delta Chief Executive Officer Ed Bastian said in an interview. “It’s an indication of a great partnership with Airbus and the recognition that we’re playing the long game and are still going to take these aircraft.”

Delta dropped 2.4 per cent to US$31.87 at 1:59 p.m. in New York. The shares tumbled 44 per cent this year through Monday, in line with the decline of a Standard & Poor’s index of nine U.S. airlines. Airbus fell 3.5 per cent to 63.68 euros in Paris.

The Delta deferrals, which include 77 aircraft that were to have been delivered through the end of next year, underscore the pressure on Airbus and rival Boeing Co. to preserve orders even as their customers have little need for new aircraft. Delta is also planning to retire 400 planes by 2025, including 200 this year.

Airbus has been in talks with a number of airlines, but doesn’t comment on individual customers, a spokesman said.

Slower Burn

Delta is the first major U.S. airline to report third-quarter earnings, setting the tone for an industry that has been slammed by the pandemic. Bastian said Delta wouldn’t be able to break even on a cash-flow basis until next year, updating an earlier forecast that the company would reach that milestone by the end of 2020.

“We are not surprised to see the target slip, given where we are today in terms of demand,” Helane Becker, a Cowen & Co. analyst, said in a report. “Delta will need some rebound in business and international travel before cash-flow break even is achievable.”

Daily cash burn will average US$10 million in December, and US$10 million to US$12 million for the fourth quarter as a whole, Bastian said. That’s down from US$24 million in the third quarter. Delta lowered operating costs 50 per cent in the three months ending Sept. 30 from the same period a year earlier.

“We’re getting a pretty good line of sight to break even by the spring,” the CEO said regarding cash burn. “The fact that we get down to US$10 million is pretty darn good when we were at US$100 million in March.”

‘Year of Recovery’

Revenue will hit as much as 35 per cent of year-earlier levels in the fourth quarter, up from 10 per cent in the second quarter, Bastian said. He expects continued improvement over the next six months as travel edges up one per cent to two per cent a week, with 2021 a “year of recovery.”

The carrier is “seeing good booking momentum” for the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays, and even into late December and early January when travel normally slows, President Glen Hauenstein said on a call with analysts. But Bastian cautioned that it could be “two years or more” before the carrier reaches a normalized revenue environment.

Delta reported an adjusted third-quarter loss of US$3.30 a share, worse than the US$2.97 shortfall that was the average of analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg. Adjusted revenue plunged 79 per cent to US$2.65 billion, while analysts had expected US$3.12 billion.

The results excluded pretax charges of about US$4 billion from the cost of fleet restructuring as well as voluntary worker retirements and separation programs. Those items were partially offset by aid from the federal government that was recognized in the quarter, Delta said. The company had US$21.6 billion in liquidity as of Sept. 30.

Cash Preservation

About 58,000 workers have left the carrier voluntarily, including 18,000 permanent departures. Those reductions are enabling Delta to avoid layoffs among most workers, including flight attendants, mechanics and baggage handlers, until the start of next summer at the earliest. The carrier remains in talks with its pilots union and has deferred furloughs until Nov. 1.

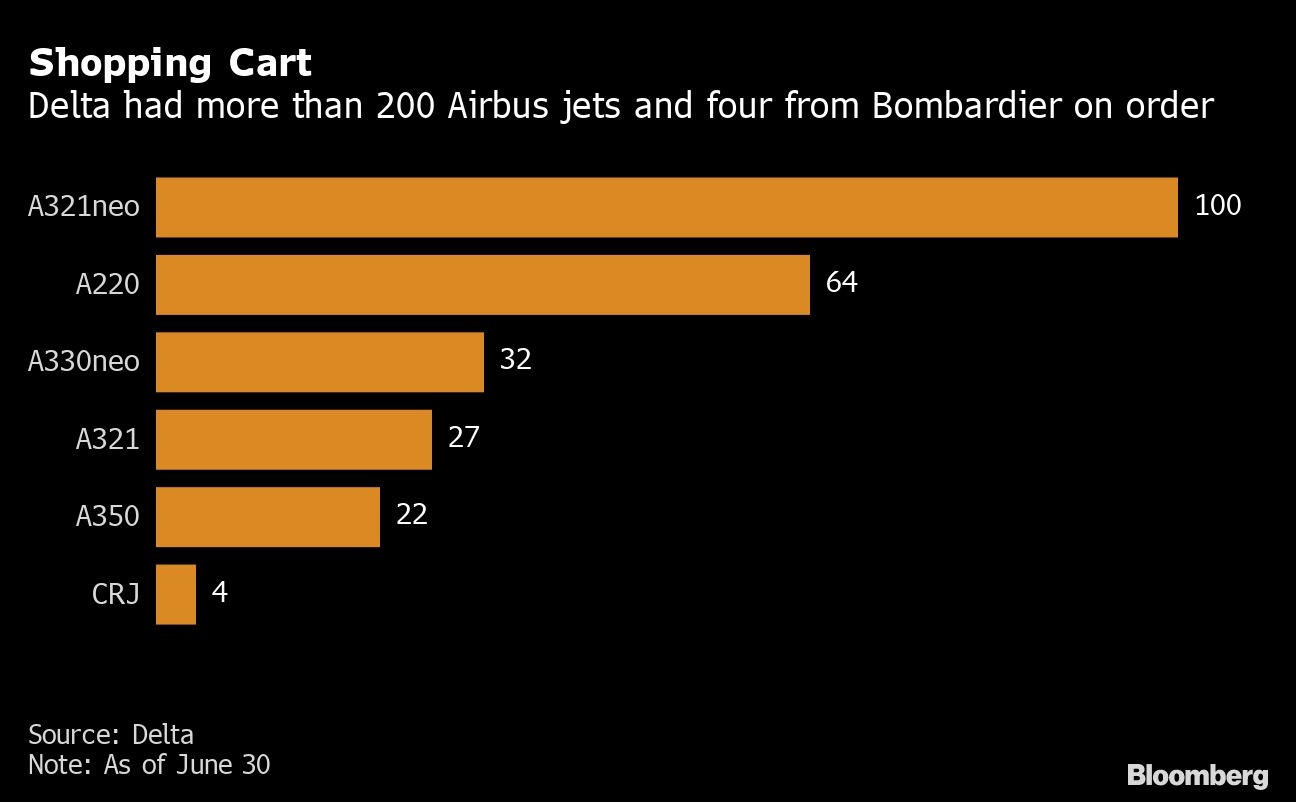

Delta’s aircraft deferrals are meant to complement the other efforts to preserve cash. As of June 30, Delta held US$14.2 billion in commitments for aircraft purchases, including US$2.35 billion in the second half of this year. Almost all of Delta’s outstanding orders are for Airbus planes, and most are due to be added to the carrier’s fleet through 2022.

Through June, Delta’s overall delivery schedule included 100 of Airbus’s single-aisle A321neo planes, 27 of its A321 jets and 64 of its A220 aircraft. Delta is also a major customer of twin-aisle planes, with commitments for 32 of Airbus’s A330neo jetliners and 22 of its A350 planes.

Delta had also been set to take four CRJ regional jets. Bombardier sold maintenance and support activities for the program to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. earlier this year while agreeing to assemble the remaining planes on order on behalf of the Japanese company.

--With assistance from Will Davies.