Dec 13, 2019

Reinhart Warns Argentina May Repeat 15-Year Bond Holdout Saga

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Argentina may be headed for an even nastier debt battle than the 15-year holdout saga that began in 2001, according to Carmen Reinhart.

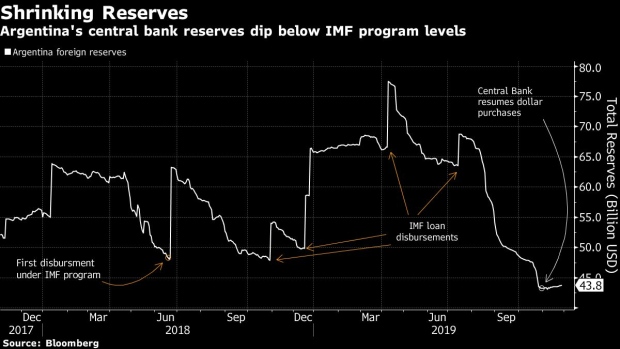

In fact, the Harvard University economist says the South American nation is starting off weaker than during its previous default drama. Its inflation rate is higher, commodity prices are lower and the debt stock is more complex. Meantime, the nation appears to be locked out of capital markets once again, meaning the International Monetary Fund isn’t likely to offer fresh financing.

“I think they’re worse off,” said Reinhart, who was deputy director of the IMF’s research department during Argentina’s 2001 crisis. “Back then, they got lucky with commodities, government revenues and their capacity to bring in dollars. I don’t think they’ll be so lucky this time.”

One Country, Eight Defaults: A Look at the Argentine Debacles

President Alberto Fernandez’s administration, which took office Tuesday, faces an early test after signaling it will open talks with creditors to delay debt payments. Next month, the Province of Buenos Aires, home to 40% of the nation’s population, owes about $571 million in payments to bondholders. Reinhart said the federal government is in no position to bail out the province, and it’s only a matter of time before the sovereign defaults on its external debt.

Fernandez is taking over an economy poised to contract for a third year. Unemployment is hovering over 10% and annual inflation is running above 50%. The nation’s dollar bonds due in 2028 fetch just 42 cents on the dollar as investors brace for a default.

By Reinhart’s estimate, investors should expect to recoup no more than 50% of their holdings, a bigger haircut than recent debt restructurings.

Fine Print on Argentine Bonds Becomes Crucial as Default Looms

One difference with the 2001 default is Argentina’s use of collective-action clauses. At the time, the nation’s notes didn’t have any rules that would compel investors to accept a deal if a super-majority of creditors agreed. That created the class of so-called holdouts who didn’t take part when the country struck a deal with the owners of about 93% of its debt.

Still, Reinhart said the variety of Argentine bonds outstanding -- from local to foreign-law and notes tied to the nation’s benchmark interest rate and gross domestic product -- increases the likelihood of holdout creditors.

“It doesn’t appear they learned anything from their last experience,” she said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Ben Bartenstein in New York at bbartenstei3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Carolina Wilson at cwilson166@bloomberg.net, Alec D.B. McCabe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.