Aug 22, 2021

Sweden’s Departing Prime Minister Paves a Path for Finance Chief

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The resignation by Sweden’s Stefan Lofven brings the largest Nordic economy a step closer to its first-ever female prime minister, and with it the task of fixing an ailing political system.

Lofven unexpectedly announced in a Sunday speech that he will step down in November after seven years in power and also quit as the leader of Social Democrats, which dominated Swedish politics for the past century. His minority coalition faced an autumn struggle to pass next year’s budget and the prospect of a defeat from the conservative-nationalist opposition in the 2022 elections.

His obvious heir is the Harvard-educated Finance Minister Magdalena Andersson, who has held the reins of the Swedish economy throughout the pandemic. A staunch advocate of fiscal prudence, she was criticized by economists before the coronavirus crisis for building up unnecessary surpluses as public debt shrank to historically low levels.

“If she wants to, I believe she will be nominated and the question is then if she’ll be appointed in unity and with a strong mandate by the congress,” said Ulf Bjereld, a professor of political science at Gothenburg University.

Lofven, the great political survivor, came to represent the impasse that Sweden found itself in. Its economy has been among the most resilient to the pandemic thanks to prudent public finances, yet Swedish society struggled to deal with an open-door policy that strained its generous welfare state and stoked anti-immigrant sentiment.

To be sure, a precedent of women leading governments has already been set in the Nordics so that aspect is unsurprising. Norway, Denmark, Finland and Iceland are now run by women. As for Andersson, she declined to comment on the political situation. Her spokesman said she was busy preparing the budget.

Earlier this year, she became the first woman to chair the International Monetary and Financial Committee, the main advisory body to the Washington-based IMF.

What is less clear is how markets will react to the latest Swedish twist. In the recent past, stocks and bonds have been impervious to political shenanigans.

Nordea Bank’s economist Torbjorn Isaksson foresees a business-as-usual scenario: “The Swedish economy has recovered from the pandemic and the public finances are robust with low debt and a relatively modest budget deficit of around 2% of GDP this year, making the Swedish krona exchange rate and interest rates resilient to the political turbulence.”

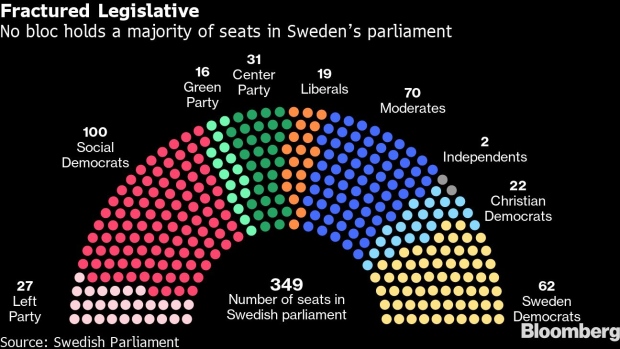

The bigger question is where Sweden goes from here and how it builds toward a more sustainable future that isn’t punctured by all-to-frequent government collapses and political paralysis. The Social Democrats currently control about a third of the seats in parliament in partnership with the Green Party.

But the reality is that the government’s handling of the pandemic and the rise in the polls of the Swedish Democrats, whose roots date to the neo-Nazi movements, have taken a toll on the electorate. Their popularity demanded a change of tack that eventually precipitated the end of Lofven, a political career too linked to the past.

The Social Democrats, credited with a generous welfare state paid by some of the world’s highest income taxes, are also a party that owes its political success to an industrial backbone that no longer exists.

If the budget doesn’t pass, or if there is another misjudged step, Sweden could face its first snap elections since 1958.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.