Apr 10, 2024

Billionaire Drahi Leaves Creditors Flummoxed With his `Bully-Boy’ Moves

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Patrick Drahi was uncharacteristically chatty on that mild March day at the headquarters of his flagship company Altice France in the south of Paris. The tycoon had just agreed to sell his media operations to fellow French billionaire Rodolphe Saadé for €1.55 billion ($1.68 billion), and was bidding adieu to managers and anchors of the news channel BFMTV.

Over bite-sized appetizers and sparkling water in a bright, glass meeting room overlooking a terrace, he told them he decided in July to cash in on the news channel, after Altice co-founder Armando Pereira was arrested in Portugal for alleged corruption. “When you have an apartment, and you realize the bathroom is worth more than the whole apartment, what do you do?” Drahi asked. He went on say that he’s been thinking about his succession and decided to start selling chunks of his empire, including the French media business, because his four kids told him they want to invest in other areas, according to people who were present but didn’t want to be identified describing a private event.

Just a short while after that gathering on March 20, Drahi’s financial adviser Dennis Okhuijsen, Altice France Chief Financial Officer Malo Corbin and group treasurer Gerrit Jan Bakker dropped a bombshell. On the company’s earnings call, they painted a gloomy picture for it in 2024, and told creditors they’d have to take a hit in the restructuring of its €24.3 billion debt pile. Proceeds of the media unit sale may not be used to cut debt, they suggested, unless creditors took haircuts for Altice France to hit its goal of a debt ratio below 4 times Ebitda from 6.4 times now.

It was a complete about-face by Drahi, who told investors in September that he was selling assets because de-leveraging Altice was his top priority. Mark Chapman, an analyst at CreditSights, called it “a monumental bait and switch” and “bully-boy tactics.”

To some Drahi observers, his plan to try and sell most of his group has emboldened him to burn bridges with creditors, who over decades bankrolled his debt-fueled empire-building. Inspired by “cable cowboy” John Malone, who pioneered leveraged buyouts of telecoms firms in the 1980s, Drahi created a group that was among Europe’s most indebted companies and one of the region’s largest junk-rated borrowers. The 60-year-old tycoon cobbled together a telecoms and media group with more than $60 billion of debt, making him a poster child of the free-money era. But rising interest rates and the poor performance of his telecoms business thrust the billionaire into a corner, prompting Malone to say in a CNBC interview in November that Drahi’s operations were “toast.”

“I think he’s at the end of his rope,” says Alain Minc, an adviser to French presidents as well as some of the country’s biggest companies, who noted that he was shocked by the way Drahi had turned his back on creditors. “It looks like he wants to save a few billion and call it a day.”

Altice France representatives declined to comment on the factors behind Drahi’s proposals for creditors or on his plans for his group.

In his heyday, some of the world’s largest banks had celebrated Drahi’s moves, praised his business acumen and pumped him with high-yield debt. Now, with his fortunes waned, his efforts to make his creditors take a hit are only logical, financial advisers close to the tycoon say, adding that it’s naive to expect otherwise.

“Ultimately, the company is over-levered and at this point a debt haircut might be one of the few options that remain,” said Haidje Rustau, a senior credit analyst at Lucror Analytics. “The documentation for the bonds is very loosely crafted and this limits creditors’ options.”

Altice France bonds had rebounded following an agreement to sell a majority stake in its data centers and the deal to offload the media business because investors had expected the company to use the proceeds to repay debt. The earnings call reset those expectations and the bonds plunged, with some falling to below 30 cents on the euro.

“What’s a bit confusing, is why you think creditors should have to share the burden to get leverage down, but equity holders should not,” Vicki Gedge, an analyst at PIMCO, said on the call.

Bondholders are banding together to squeeze out better terms. Creditors with a majority of Altice Holdco bonds with material holdings in Altice France have come together to pursue a consensual deal among creditors, a spokesman for investment bank Houlihan Lokey Inc. said in an emailed statement. Houlihan Lokey is advising the group alongside law firms Milbank LLP and Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP. A separate group of senior creditors is being advised by law firm Gibson Dunn & Crutcher LLP.

Also Read: Millennium Shuts Feasey’s Credit Trades After Altice Bets Sour

Altice France, which controls French mobile operator SFR and Altice Media, is one of the three silos of Drahi’s telecommunications and media empire, the others being Altice International and Altice USA. By turning Altice Media into an “unrestricted” asset, Drahi has ensured that the proceeds from its sale can go to things other than paying down debt. The decision to use that tactic as a bargaining chip has angered creditors because in the event of a bankruptcy, such assets would be owned by them.

“He is engaging in a tug-of-war with bondholders,” said Stéphane Beyazian, an analyst at Oddo BHF. “Usually, the sale of assets should be paying off the debt. What his move could suggest between the lines is that, if bondholders don’t work with him, he could look at various options for his cash, one could even be upstreaming the cash in the holding companies.”

Debt holders would like to see Drahi to meet them half way. Some say if the group sells its Portuguese unit, which is part of Altice International, and adds it in the mix for Altice France, Drahi would be bringing in some equity, making the demands he makes of bondholders more palatable.

Debt holders have been trying to get to the bottom of Drahi’s volte-face. Some see the move as a way for Drahi to preempt a discussion that could end up with a court-appointed mediator. Others wonder if it’s a tactic to force debt prices down and have more negotiating power.

“It’s very possible that it’s part of Drahi’s negotiation strategy and the haircut will be smaller and everyone accepts it in the end,” said Lucror’s Rustau.

Whatever the reasoning, people who have worked with Drahi note that he can be ruthless in business, and has a singular attitude toward debt, living up to the adage that if you owe $1,000, it’s your problem; when you owe $1 billion, it’s the bank’s problem. In 2016, he provided a rare glimpse into his views on debt. Addressing students at his alma mater, the elite French university École polytechnique, he recounted how he had bought his primary residence entirely on credit when he was in his twenties.

“What’s the worst that can happen? At worst, the bank gets the house back, but that will never deprive me of the happy years I’ve had in the meantime,” he said.

That said, some investors say the damage to his reputation from his recent actions will cost him. Even if Altice France manages to cut the roughly €10 billion needed to get to the new leverage target, it still has a big debt pile to refinance over the next two-to-four years. Already, credit ratings of the holding company Altice Holdco and Altice France have been slashed by both S&P Global and Moody’s Ratings to the CCC area, the lowest level in junk debt, making any new borrowings both harder and more expensive.

Still, there will always be yield-hungry investors out there, others say, arguing that markets have the memory of a goldfish.

“A common feature for individuals like Drahi is that they rely on capital markets and try to remain on good terms with them. That contract works when they want to go back to the market. But he might also be speculating that after a few years greed takes over fear and investors will have forgotten,” Rustau said.

Drahi has been aggressive with his creditors before. When his company Numericable needed to restructure its debt in 2009, instead of meeting creditors — many of whom were based abroad — in central Paris, he invited them to the company’s headquarters in Champs-sur-Marne, some 30 kilometers outside the French capital, according to people involved in those discussions. Coming during the financial crisis, Drahi’s demands for changes in the covenants and extension of Numericable’s debt were seen as logical, but the venue he had chosen for the meeting was seen as pure power-play.

But his current hardline tactics have taken things to a new level, and come as he sells assets with an eye on his succession. Although his children work alongside him in his telecoms, art, real estate and philanthropic businesses, they are keen to explore other fields, he said at his media group gathering. The mogul said he doesn’t want to find himself in the situation faced by 78-year-old businessman Jean-Charles Baudecroux, who waited too long to sell his media assets NRJ TV and radio in France — assets Drahi had once coveted.

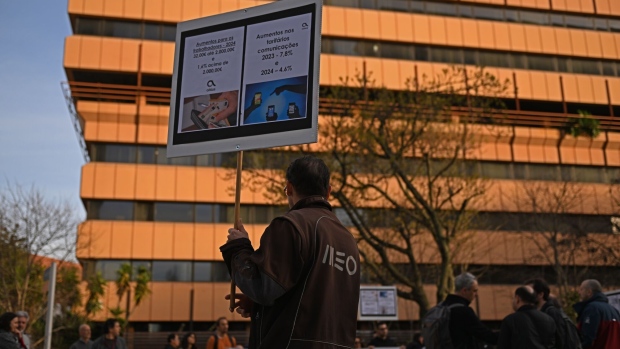

A French-Israeli, Drahi often spends time in Tel Aviv, where his daughter Graziella got married a week before the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks. He has been mostly working from Israel and Switzerland these past months, focusing on M&A operations, people familiar with the matter said. The biggest deal on the table is the sale of his Portuguese carrier Meo, with Saudi carrier STC in the lead to buy it, Bloomberg has reported. In France, Drahi is working on letting funds take a stake of the group’s fiber network unit XpFibre, which could fetch him at least €3.5 billion. His French phone unit SFR continues to bleed subscribers, leaving unions wondering how it can recover without investments.

“We are very concerned about the company’s situation and the straitjacket we find ourselves in,” said Olivier Lelong, a representative of the CFDT union. “The debt has to be repaid, which we have been calling for for years... Patrick Drahi is now putting pressure on his financiers. Is it to free up room for maneuver, or something else? We’re not being told. It gives the impression that he has no real alternative but to use force to loosen the noose.”

To top all that, there is the looming corruption case, which could bring potential risks for investors. The scandal linked to alleged corruption in the company’s procurement chain started in Portugal and has now spread to France, with French financial prosecutors beginning their own investigation in September. Altice has cut ties with executives and suppliers mentioned in the investigation, but prosecutors will take some time to determine the extent of the corruption system that has allegedly been running deep inside the company over several years, both in Portugal and France. Drahi himself is not accused of any wrongdoing, and Altice sees itself as a victim in the case.

It also remains to be seen whether Drahi will indeed sell the telecoms empire he built over the last three decades. The tycoon, who’s also an art collector, wants to hang on to his auction house Sotheby’s — probably his most prestigious asset.

At the BFMTV channel farewell drinks, first reported by French media outlet L'Informé, he told his guests he wants to focus on the problems in the Middle East. He said he wants to spend more time in Israel, seeking to make an impact on the situation there and help bring peace in the region. Drahi owns Israel’s national carrier Hot and i24NEWS, a news channel broadcasting from its Jaffa Port headquarters in Tel Aviv in Arabic, English and French, and soon in Hebrew. He also said that he wanted to invest in the Gulf area, and has excellent ties with Saudi and Emirati leaders.

Don’t count on him to reveal the details of his plans as he reshapes his empire, warns Minc.

“He always keeps his cards close to his chest — something bankers don’t like.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.