Apr 4, 2024

CIBC CEO Dodig says multiple rate cuts this year are unlikely

, Bloomberg News

TD Bank, CIBC beat Q1 EPS expectations

Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce Chief Executive Officer Victor Dodig doesn’t expect a flurry of interest-rate cuts any time soon.

“I’ve never been of the view that there’ll be multiple cuts this year,” he said in an interview after the bank’s annual general meeting at its Toronto headquarters.

Dodig said he does think that economic conditions will soon merit action by the Bank of Canada and other central banks, citing rising unemployment and slower year-over-year wage growth, as well as inflation edging closer to the 2 per cent target. While policymakers probably won’t wait for that goal to be reached before cutting rates, he said, their reductions are unlikely to be particularly aggressive.

“I think we’re going into a world where the back half of this year is likely to see a rate cut — maybe two — in these major developed economies like Europe, Canada and the United States,” Dodig said.

Dodig’s comments reflect growing doubts about how quickly borrowing costs will fall in 2024, given better-than-expected growth and rising uncertainty about the path of inflation. Still, his predictions are at odds with the median estimate of economists in last month’s Bloomberg survey, who expect 100 basis points of cuts by the Bank of Canada’s December meeting. Traders in overnight swaps are pricing in between 50 and 75 basis points of cuts by that time.

But views vary elsewhere. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Neel Kashkari said Thursday that rate cuts may not be needed this year if progress on inflation stalls, especially if the economy remains robust.

No matter what happens with cuts this year, “Canadians have been responsible in adjusting” to the current interest-rate environment, Dodig said. “They’ve taken their own what I call anti-inflationary actions.”

Most people are working, many still have savings from stimulus spending and CIBC clients have slashed their own discretionary spending to counter the higher cost of goods and elevated mortgage expenses, he said. And, he added, delinquencies are “not anywhere near the pre-pandemic levels.”

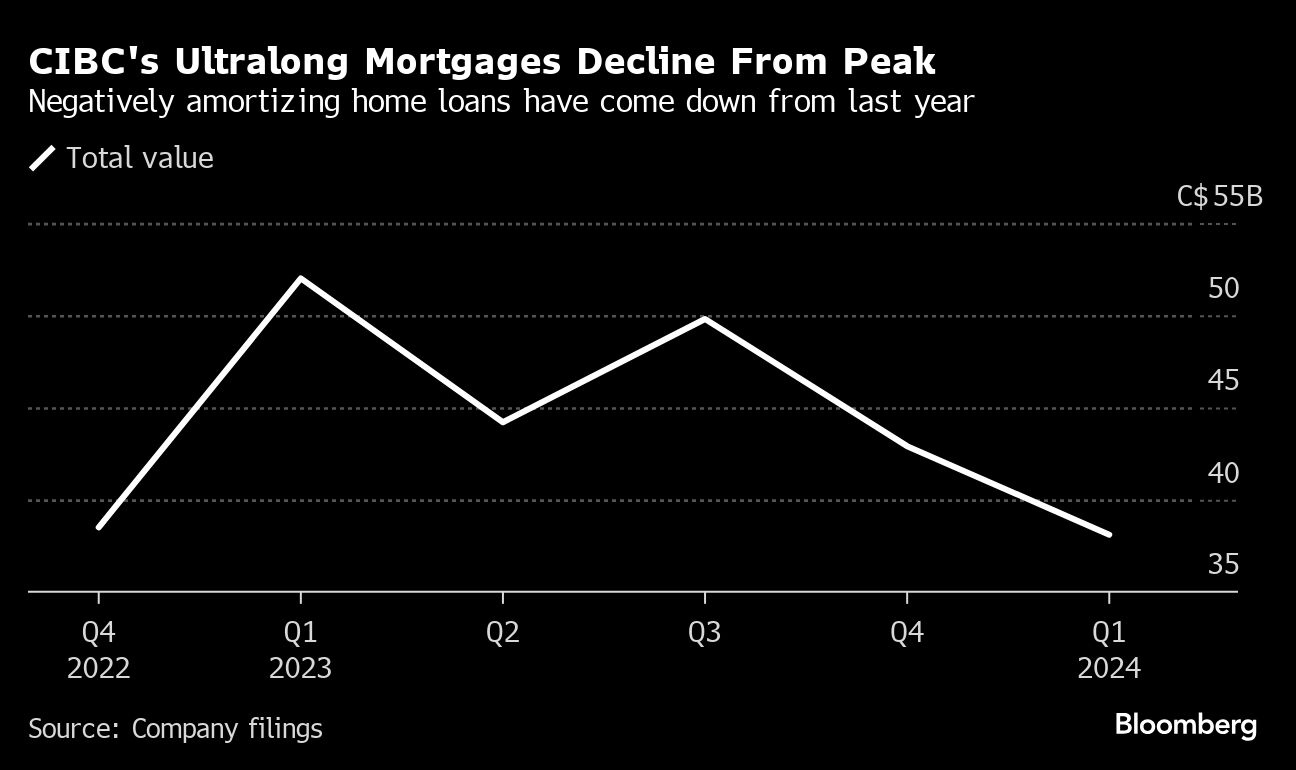

CIBC, Canada’s fifth-largest bank, is heavily exposed to the country’s mortgage market, and many of its customers with variable-rate mortgages have faced challenges amid the rapid increase in rates in recent years. For those borrowers with variable-rate loans and fixed payments, the set monthly fee was no longer enough in many cases to cover the rising interest costs, so their amortization period — the time needed to pay off the loan — began to lengthen, growing by decades in some cases.

The lender had $52 billion (US$38.5 billion) in so-called negatively amortizing mortgages by the end of the first fiscal quarter of 2023. One year later, that was down to $38.1 billion, according to the bank’s filings.

Dodig said the bank has seen its clients “take action on their own” to address negative amortization on their mortgages. Moves could include making larger payments.

Canada’s banking regulator has warned about the dangers of fixed-payment, variable-rate mortgages, which have great appeal when rates are low but have proved painful as rates soared. Still, Dodig said, the bank will continue to offer them because customers prefer to have options. He also noted that the regulator has policies requiring banks to hold more capital against such mortgages.