Mar 17, 2022

China Credit Investors Find Themselves at Back of the Line

, Bloomberg News

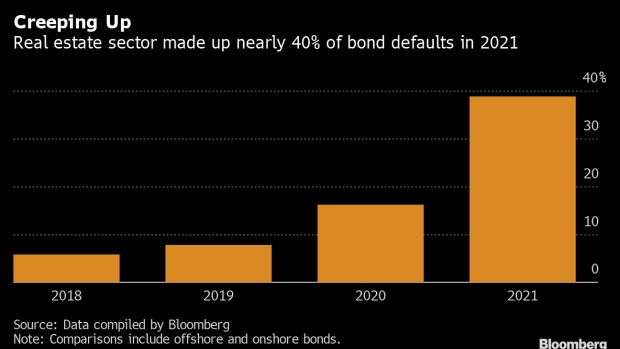

(Bloomberg) -- Investors in China’s $870 billion of offshore bonds are facing up to the realities of being last in line as borrowers struggle to pay during an unprecedented wave of distress that’s sent defaults to a record.

Already behind their onshore peers in the pecking order, hurdles faced by dollar-note holders in their efforts to claw back money are growing. They include backroom deals that give priority to undisclosed private lenders, unfavorable extensions and payment delays -- all underscoring poor governance at debtors and the diminished power of creditors.

The new reality comes in the wake of China’s property-market collapse, a result of Beijing’s crackdown on leverage and the ensuing credit crunch. What was once one of the world’s most-profitable corporate debt markets has turned sour for many global investors. Since the crisis started to flare up in November, holders of more than 350 China real-estate offshore bonds suffered as much as $87 billion in potential mark-to-market losses, according to Bloomberg Intelligence estimates earlier this month.

At least 18 developers have sought to delay payments on offshore debt since September, according to data compiled by Standard Chartered Plc and Bloomberg. More than a dozen have defaulted. While onshore creditors are also weathering the same storm, their recovery rates in out-of-court settlements have historically been higher, with some paid in full, Fitch Ratings said in September.

“Companies have investors by the throat because on one hand they have no money and in some cases no willingness to pay, while on the other hand they know that investors cannot stomach a full default,” said Raymond Chia, head of credit research for Asia ex-Japan at Schroder Investment Management.

Many builders have sought to kick the can down the road by swapping imminently maturing notes with those due later in a bid to avoid outright delinquency. In the meantime, investors stung by months of losses are keen to avoid messy failures that could trigger cross-defaults. Pushed to a tight corner, they’re often left with little room to negotiate better terms on a deal.

In January, Guangzhou R&F Properties Co. purchased just 16% of the principal on a $725 million note in a tender offer after originally saying it had set aside $300 million for the buyback. The remaining debt was then extended by six months. While no creditors actually voted for the option, those who decided to tender their notes were also “deemed to have voted in favor” of the delay.

The developer has to service at least 6.55 billion yuan ($1.03 billion) in local bond obligations before settling the extended offshore note in July, Bloomberg-compiled data show. The firm’s dollar note due 2023 has fallen to about 14 cents on the dollar from 37 cents at the beginning of the year. Since its extension, the bond now due in July has fallen 73% to 18 cents.

Still Addicted

Some of the pain for offshore bondholders may be self-inflicted, said Chia. After earning billions of dollars trading Chinese high-yield bonds over the years, investors continued to bet on them even as they saw “structures become looser and looser -- especially since 2016 with lots of covenant relaxation,” he said. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates that funds around the world have increased their exposure by about $4 billion since the crisis started, with U.S.-based giant BlackRock Inc. leading the charge.

Flimsier types of protection such as “keepwell” provisions -- essentially a gentleman’s agreement to protect foreign bondholders in case a mainland company runs into financial trouble -- have become less popular, with issuance of such notes on pace to fall for a second year.

Dip-buyers got a new reason to cheer this week. China’s call for new policies to help support the battered property sector and a pledge to boost financial markets spurred a rally in the bonds of stronger developers, though gains in the broader high-yield market were muted.

Supportive measures may be too little, too late according to analysts. Looming and lingering risks include the fallout of Russia’s war in Ukraine, a potential decoupling of the Chinese economy from the U.S. and President Xi Jinping’s broader crackdown on businesses to ensure the primacy of the Communist Party as part of his “common prosperity” campaign.

Disgruntled investors are beginning to fight back, but it’s not clear if they’ll have much success. A group of bondholders engaged a law firm to hold talks with Guangzhou R&F about the deal, Debtwire reported in January. Yuzhou Group Holdings Co., after winning the approval of a majority of creditors to exchange two dollar bonds, said it wouldn’t pay those who decided not to participate. The builder may now be facing legal action.

There’s also little incentive for borrowers to preserve good relations with offshore investors to ensure support in future bond sales. That’s because offshore primary markets are effectively shut to most developers for the foreseeable future after the clampdown drove borrowing costs to prohibitive levels for high-yield securities.

Another complication is hidden debt. Opaque liabilities that may or may not be reflected on the books of borrowers make it hard for investors to assess where they stand in the capital structure or what payments take precedence.

Once seen as one of China’s stronger developers, Logan Group Co.’s ratings were slashed deep into junk territory in a matter of weeks as reports emerged on undisclosed leverage. The firm earlier this year denied it had privately placed debt. Logan is said not to have paid a loan due last week that backs a private bond it guaranteed, according to REDD.

“Companies haven’t been transparent about their private debt and upcoming payments, but the market’s also been rife with rumours supposedly linked to short-selling,” said Anthony Leung, head of fixed income at Metropoly Capital HK Ltd. “The lack of transparency has led to a vicious cycle of panic selling and a collapse in the price of securities, which closes refinancing channels.”

Concerns have also cropped up that creditors holding opaque debt might receive preferential treatment, with developers opting to repay those obligations while skipping or extending deadlines for its publicly held offshore bonds. Only weeks after assuring investors it had sufficient working capital and wasn’t facing any cash squeeze, Fantasia Holdings Group Co. defaulted on a public note. It told Fitch that it repaid a private bond just days earlier.

Onshore bondholders can sometimes continue to receive payments, even as borrowers overlook offshore debt. China Evergrande Group paid interest on a local bond even after it had missed coupon payments on several dollar notes.

“Hidden debt worries aren’t new in China,” said Leung. “But when companies come close to the brink of collapse, it becomes even harder to tell what news is real or fake.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.