Oct 15, 2022

Ukraine IT Sector Tested as Putin Bombs Civilian Infrastructure

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Oleksandr Ruban, the chief executive officer of an Odesa-based firm that provides communications technology services, was ready when a Russian missile this week left one of his offices in the dark and offline.

After the strike knocked out power, Ringostat’s four employees at its Cherkasy office fired up a diesel generator and their Starlink terminal, and continued to support clients from Canada to Kazakhstan who in many cases didn’t know the services were coming from a war zone.

Ruban’s contingency planning is an example of how Ukraine’s IT industry has managed to be a rare bright spot amid the country’s economic collapse following the Russian invasion. But the sector, already navigating a loss of talent and investor jitters due to Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War II, this week had to contend with a wave of internet and power outages as Russia renewed attacks on cities far from the front.

“We had a dream that one day IT will become Ukraine’s leading industry,” said Roman Prokofiev, co-founder and CEO of job search website Jooble, which operates in 69 countries. “We didn’t wish this dream to come true this way.”

The Kremlin this week targeted civilian infrastructure across the country, killing at least three dozen people, after President Vladimir Putin accused Ukraine of carrying out an attack on a road and rail bridge to Crimea, a Black Sea peninsula Russia annexed in 2014. Kyiv hasn’t claimed credit.

The strikes led to power outages in many cities, including the capital Kyiv and Lviv, an IT center in the west that hosts many professionals seeking refuge from the fighting.

Without electricity, Starlink satellites are for many the only way to connect to the internet. Yet, the service’s future in Ukraine is in question after SpaceX CEO Elon Musk on Friday threatened to cut financial support in response to Ukrainian officials slamming him over comments suggesting the government cede territory in exchange a peace deal with Russia.

A prohibition on conscription-aged men leaving the country may have contributed to the sector’s resilience, according to a study published last month by Johannes Wachs, a researcher at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna. He found Russian software developers were significantly more likely to have relocated after the war began than their Ukrainian counterparts.

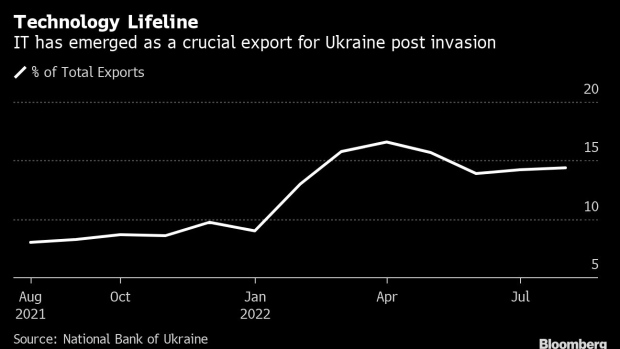

About 1.1% of Ukraine’s workforce worked in IT before the war, and sales have grown this year, with the industry becoming a key source of foreign currency as the broader economy is forecast to shrink by about a third in 2022.

Wartime Deficit

IT firms notched more than $5 billion in sales abroad in the first eight months of the year, boosting their share of the country’s export revenues to 14%, according to central bank data.

The International Monetary Fund estimates Kyiv will need at least $3 billion a month in financing next year to cover its wartime deficit.

California-based digital product engineering company GlobalLogic, which was acquired by Hitachi Ltd. last year, employs more than 6,000 people in Ukraine and has arranged diesel supplies to ensure business continuity, according to Anna Shcherbakova, the company’s head of operations in the country.

But with the war in its eighth month and showing no sign of ending, GlobalLogic’s customers are increasingly concerned about its Ukraine exposure, according to Andrii Yavorskiy, a vice-president for strategy and technology. He said the company has responded by hiring more staff outside of Ukraine.

“IT is an industry that has been operating and growing even during the war,” said Stepan Veselovskyi, the CEO of the Lviv IT cluster, a community of more than 200 tech companies. “If we lose it as well, due to power outages or internet disruptions, we’ll be forced to seek even more money from other nations.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.