Apr 6, 2024

Brazil Labor Spat Thwarts Lula’s Bid to Boost Growth and Save the Amazon

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- A labor dispute at Brazil’s environmental regulator is gumming up Latin America’s largest economy, with major oil and mining projects facing delays and imported cars piling up at ports.

Protests by government employees over staff shortages and low wages also threaten to undermine President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s bid to slow rampant destruction of the Amazon rain forest — a marquee policy aimed at restoring Brazil’s international credibility.

Officials at both the top environmental agency, known as Ibama, and the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation have dramatically reduced field inspections aimed at curbing illegal deforestation and gold mining on Indigenous lands. They’ve also halted issuing new environmental permits required to get infrastructure and industrial projects off the ground.

The disruptions, which have entered their fourth month, have delayed some of the proposals Lula’s government is relying on to boost gross domestic product and further Brazil’s green transition.

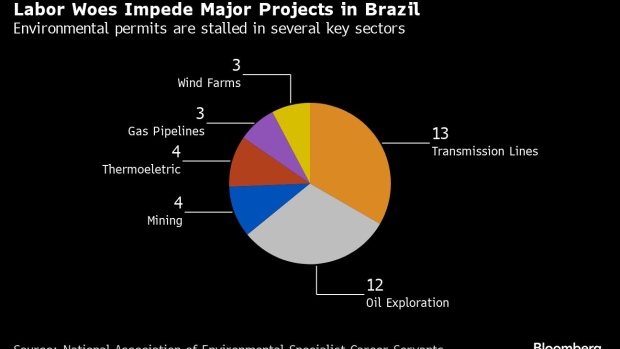

Oil companies including state-run Petroleo Brasileiro SA, BP Plc and Equinor ASA are facing long delays to secure permits to explore and drill for crude, according to Ascema, the association of environmental officials. In the power sector, four thermoelectric plants, three wind farms, 13 transmission-line projects and three gas pipelines are waiting for permits.

Progress on two mining projects spearheaded by Vale SA, the world’s second-biggest iron ore producer, has slowed. And about 16,000 imported cars have been left stranded at ports as they wait for clearance from government workers.

“A standstill for three months is bad, but if it takes more than five months it can be catastrophic,” Claudio Frischtak, managing partner at infrastructure consultancy Inter.B, said in an interview. “The delays to start operations could lead to contracts being revised and companies going to court to obtain licenses by judicial means, like an injunction, for instance.”

Ascema, which also represents the Chico Mendes Institute workers, flagged staffing levels as one of the main sticking points, along with salary discrepancies with other federal agencies. It said that since January, civil servants have been focusing on internal bureaucratic work instead of field activities and would continue doing so until they reach an agreement with the government.

“Today we have approximately 700 civil servants working in the inspection of all biomes throughout Brazil,” said Wallace Lopes, an Ibama agent and Ascema director. “The legal Amazon alone is the size of Western Europe.”

The Brazilian government said in a statement it remains sensitive to the need of federal agencies to replenish staff. It also said it’s doing what it can to meet wage demands within budgetary limits.

Latest Talks

Both sides met again Friday for three hours in Brasilia, where the government presented a new proposal. But the offer didn’t meet the workers’ main requests and would likely be rejected, Lopes said after the talks wrapped.

The first 90 days of partial work stoppage at Ibama cost an estimated 20,000 barrels of oil per day, and 3.4 billion reais ($680 million) in revenue to major producers in the country, according to the Brazilian Oil and Gas Institute. The lobby group is also concerned about delays in the licensing of new exploratory areas.

Petrobras expected an appeal for drilling permits in a key offshore basin to be resolved by February and may have to reshuffle its plans to avoid a stalled rig.

Import licenses for combustion and hybrid vehicles required to control polluting emissions have also been hit. Brazil’s carmakers association, Anfavea, estimates thousands of cars are stopped at ports since the issuance of documents is happening at a slower pace.

Chinese automakers Great Wall Motor Co. and BYD Co., which plan to start producing cars in Brazil late this year, depend on imports to supply the local market. Both companies have escaped unscathed so far, with Great Wall crediting the work it does in advance to get license approvals. The near future, however, is uncertain.

“For the next shipment we have to approve licenses now. If the strike continues it could affect us,” Ricardo Bastos, Great Wall’s institutional relations director, said in an interview.

Rio de Janeiro industry group Firjan went to court against Ibama claiming the failure to grant vehicle licenses may extend to a halt in production in neighboring Argentina, which sends a large part of its output to Brazil. The stagnant cargo in Brazilian ports could produce a domino effect of production halts, interrupted logistic flows, domestic price increases and reduced foreign trade, the group said.

For Lula, the labor woes are an inherited problem stemming from the previous government’s neglect of the climate file. Brazil’s environmental agencies were partially dismantled as former President Jair Bolsonaro rolled back protections and now have only 53% of workers required by law.

The change in government produced quick results, with deforestation in Brazil falling 50% during Lula’s first year in office. But since workers halted inspections, notices of violation in the Amazon have plummeted nearly 88%, and fines issued for environmental crimes nationally have dropped 69% compared to the first quarter of 2023.

Brazil’s vast tropical rain forest stores more carbon above ground than any other ecosystem, so any rise in deforestation rates could dramatically increase global warming.

“Lula’s government has the environment as a showcase in its return to the international stage,” said Lopes, the Ibama agent. “The ticking bomb will explode as deforestation data worsen.”

(Corrects wording of Frischtak quote in 7th paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.