Nov 15, 2023

Meloni’s Italian Deficit Outlook Isn’t So Rosy in EU View

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Italy’s debt ratio will rise in the next two years and its deficits will be wider than premier Giorgia Meloni’s government predicts, according to the European Commission.

New public-finance projections released in Brussels on Wednesday as part of the executive’s autumn forecasts for the region are less optimistic on the euro area’s third-biggest economy than those published by the coalition in Rome on Sept. 27.

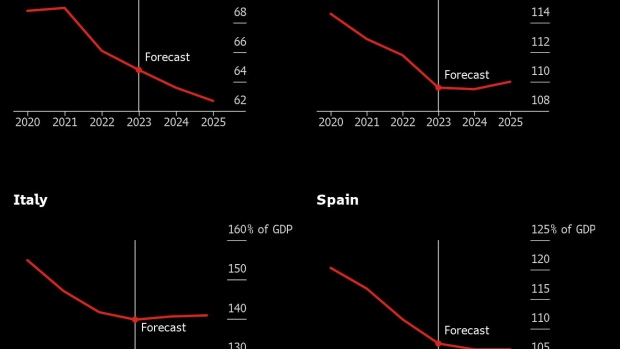

They show debt as a percentage of gross domestic product increasing to 140.9% in 2025, from a lower-than-expected trough of 139.8% this year. By contrast, the government envisages the ratio falling below 140% on that horizon.

The Commission sees the deficit narrowing less drastically to 4.3% in 2025 — a wider outcome than the 3.6% projected by Meloni and her colleagues.

Italy is in the sights of Brussels officials, ratings companies and investors after the government unveiled a loosened public finance profile for the coming years. Moody’s Investors Service has penciled in Friday as a potential moment when it could downgrade the country to junk.

Italian Finance Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti has insisted on sticking to a path of fiscal prudence, despite the longer horizon to do so. On Tuesday, he told lawmakers that the government won’t waver from that ultimate goal.

“We are fully committed to achieve the necessary fiscal adjustment to get debt sustainably lower and resilient to negative shocks,” he said.

In Brussels, Economy Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni was questioned on why the EU’s view is different to the government’s. He said officials are assuming higher debt-servicing costs in 2025 than Meloni’s coalition is, the likely renewal of a tax break that the government didn’t include, and a bigger increase for public-sector salaries.

“The difference is not enormous,” he told Bloomberg Television later. “One of the main factors is that we calculate this tax-labor reduction, and they are not yet calculating it.”

The prospect of a deficit still noticeably above 3% two years from now could prove a point of contention with the EU, given that its regime limiting shortfalls to that ceiling will kick in again as of January.

Gentiloni, a former Italian prime minister, observed that he previously served in governments that managed to achieve primary surpluses. The 3% deficit threshold is “reasonable” and after dealing with the legacy of the pandemic, Italy should aim to return to it, he said.

Euro-region finance ministers are currently at loggerheads on how the reinstated fiscal framework should be applied, a stand-off that is alarming European Central Bank officials.

Investors initially reacted to Meloni’s budget in September by pushing the spread between Italian and German bonds — a measure of sovereign risk in the region — up to 210 basis points for the first time since January. It fell below 180 basis points on Wednesday.

Giorgetti acknowledged this week that the government’s growth target of 0.8% may need to cut in light of incoming data. The Commission’s forecasts still show that Italy will avoid a recession this year and should keep growing in ever quarter through the end of 2025.

EU Recovery Fund investments will add 0.5 percentage point to growth every year, Gentiloni told reporters in Brussels.

“It doesn’t seem like a lot, but if you look at the numbers overall we can see that it’s very significant,” he said. “The most significant contribution in terms of investments from the Recovery fund is expected between 2024 and 2026.”

--With assistance from Giovanni Salzano, Alexander Weber, Jonathan Ferro, Lisa Abramowicz and Tom Keene.

(Updates with Gentiloni starting in ninth paragraph)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.