Feb 27, 2022

Putin’s Ukraine Move Fuels Shock at Home But Little Opposition

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As Vladimir Putin gathered Russia’s business elite in the Kremlin hours after he sent troops into Ukraine, executives back at the offices of the tycoons’ companies worried: would being shown at the televised meeting make them targets for Western sanctions?

The concern, relayed by several executives who spoke on condition of anonymity at the time of the Feb. 24 meeting, reflects a pervasive but powerless horror felt by some of Russia’s elite and ordinary citizens over the invasion and the sweeping international isolation it is causing.

The waves of international sanctions now in the works will isolate Russia like North Korea, said one wealthy businessman with close ties to Putin’s inner circle who himself was hit by the restrictions several years ago. But that won’t stop the Russian leader, he said. With Covid-19 restrictions increasing his isolation in recent years, Putin has grown more reliant on a small circle of hardline advisers, according to people close to the leadership.

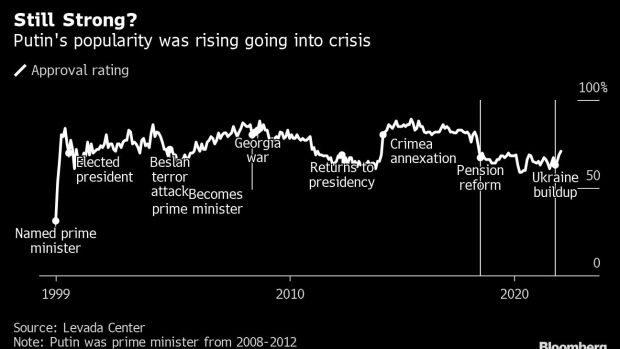

Opinion polls show public support for him grew as he ratcheted up tension with the West in January and February. But in contrast to 2014, when an overwhelming majority of the Russian population backed the annexation of Crimea, the conflict in Ukraine makes many fearful.

So far, that discontent is mostly kept quiet in a Russia, where years of increasing repression have left most vocal Kremlin opponents in jail or exile.

Scattered public protests broke out in the days after the invasion but drew modest crowds. Police detained about 1,800 people of those who did turn out. A few celebrities have come out publicly with criticism, as well, and some who protested have faced reprisals.

U.S., EU Cut Some Russian Banks From SWIFT, Target Central Bank

The impact of the sanctions, unprecedented limits hitting the country’s biggest banks and access to technology, as well as measures announced Saturday night that could largely cut if off from the western financial system and send the ruble into a tailspin, is just beginning to be felt. Though Putin has been preparing for the limits for years, the U.S. and European Union are now seeking to freeze much of his $640 billion in central bank reserves.

“It’s the Iranian scheme, which at the start leads to a steep drop in GDP and living standards before the country starts to adapt,” said Oleg Vyugin, a former top central bank official who was one of the few willing to comment publicly on the situation.

Cash Shortage

The central bank had to boost supplies of cash to banks to keep ATMs stocked as nervous Russians withdrew savings. Popular online-payment services like ApplePay stopped working. Major airlines canceled flights to and from Europe as countries closed their airspace to Russian jetliners. Access to western social networks like Twitter and Facebook was limited.

“We have to wait until some shock about what happened wears off,” said Vyugin. Opponents of the Kremlin’s military action, he said, “consider it a disastrous decision because it will have severe consequences - not only for the economy, but in terms of Russia becoming isolated and a pariah.”

Some hints of differing views have slipped out. Two days before the invasion, when it seemed briefly like tensions might ease, billionaire Oleg Deripaska wrote in his Telegram channel, “That’s it! There won’t be any war!! Now a long road to peace...”

Three days later, with Russian troops advancing into Ukraine, the post was gone. Deripaska’s spokesman declined to comment.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Thursday it would be “impossible to cut off a country like Russia with an Iron Curtain.” He didn’t mention the Soviet era.

Top officials and business figures “will stand behind Putin to the bitter end as the alternative is to go to prison,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “They’re all hostages.”

Putin’s Financial Fortress Blunts Impact of Threatened Sanctions

Putin, 69, Russia’s longest serving leader since Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, has managed to maintain a firm hold on power despite stagnant living standards. His gamble to defy international opinion and use force to overthrow the Ukrainian government may be the biggest risk yet in his more than two-decade-long rule.

“The war will polarize society -- the anti-Putin minority will grow even more disenchanted,” said Tatiana Stanovaya, a political consultant and founder of R. Politik. “But it’s unlikely as of today to lead to any major changes in the near future as the authorities will stamp out all criticism.”

A poll published on Feb. 24 that was conducted by the independent Levada Center showed that 51% of Russians are frightened by the prospect of hostilities with Ukraine. “Even if they blame Kyiv and the West for it, it doesn’t mean they support the war,” said Stanovaya.

The Long History of Sanctions Aimed at Putin’s Russia: QuickTake

But support for Putin rose in the early part of this year as tensions built and many Russians accept the Kremlin’s line that western sanctions would have come in any case, according to Levada Director Denis Volkov.

“People haven’t realized the full impact of the sanctions and the number of casualties in Ukraine,” he said. “A lot will depend on how long this war lasts and how many more people it affects.”

With the Kremlin determined to control the narrative at home, Russia’s media regulator on Saturday ordered ten mostly independent news outlets to remove reports of alleged civilian casualties and attacks on cities by Moscow’s forces in Ukraine. The authorities also started restricting access to Facebook after owner Meta refused to stop fact checking and labeling content posted by four Russian state-owned media organizations.

Other media said they were being ordered to delete references to “war” and “invasion” and use the Kremlin’s preferred term: “military special operation.”

Reinforcing the warning to keep in line, the Foreign Ministry expelled Elena Chernenko, a foreign affairs columnist at the Kommersant newspaper, from the pool covering Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov because she organized a petition signed by some 300 reporters and experts against the war.

Putin set the tone on Feb. 21 at a televised meeting with top officials ahead of the military operation.

When Sergei Naryshkin, the foreign-intelligence chief, cautiously suggested that it might be worth giving diplomacy another chance, Putin cut him off abruptly.

“Are you suggesting starting negotiations?” Putin asked. “Speak directly, Sergei.”

Naryshkin quickly backtracked, so visibly flustered that he endorsed annexing the Russian-backed separatist zones in eastern Ukraine instead of just recognizing their independence. That prompted another scolding from a smiling Putin: “That’s not what we’re talking about.”

Naryshkin, his voice shaking, again clarified that he backed the decision. “Good,” Putin said. “Now sit down.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.