Apr 6, 2022

Federal budget will complicate Bank of Canada inflation fight

, Bloomberg News

Trudeau budget may complicate Bank of Canada inflation fight

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland may effectively tell the Bank of Canada it’s on its own in tackling inflation when she introduces a budget Thursday that’s expected to be full of new spending initiatives.

In the lead-up to the release, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has indicated it remains more committed to delivering new social programs than repairing fiscal damage from the pandemic or cooling an overheated economy.

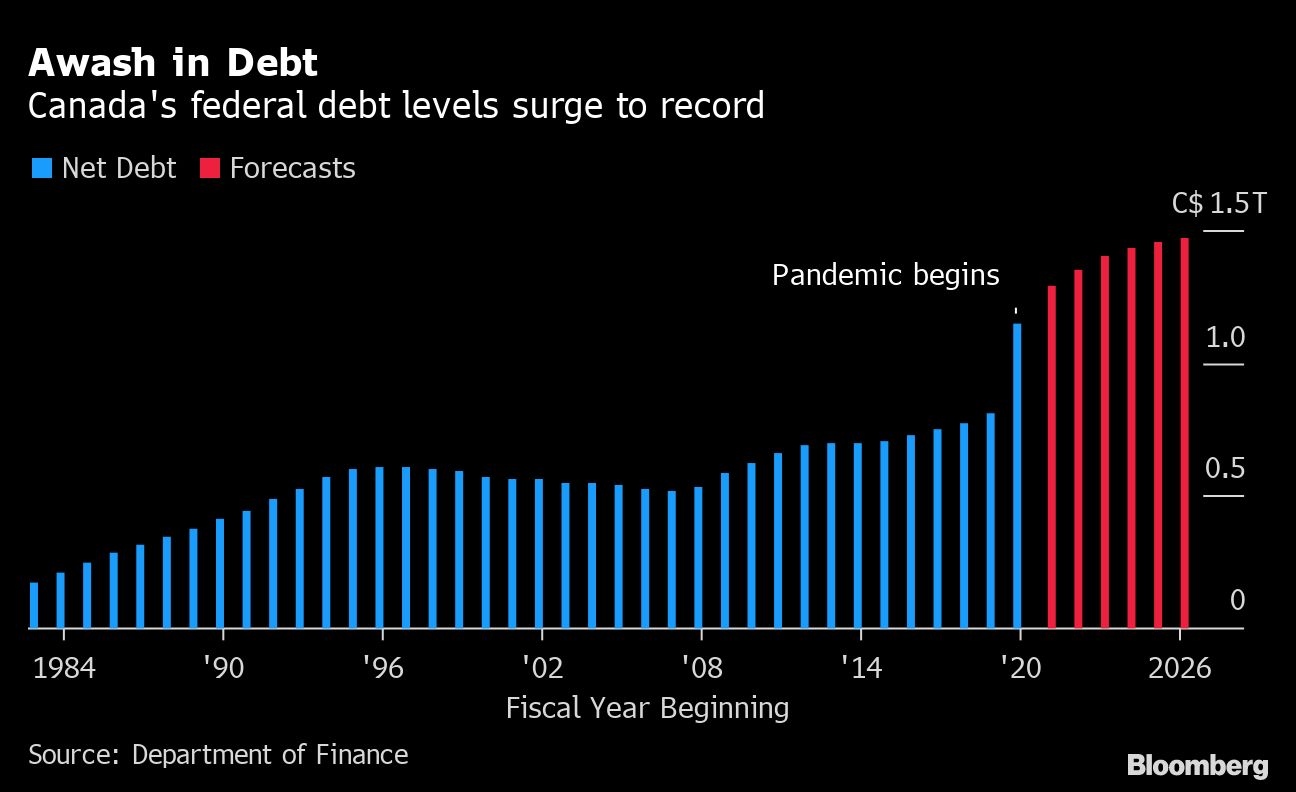

Bank of Nova Scotia predicts Freeland will put the government an additional $40 billion (US$32.1 billion) in the red over the next five years, despite a surprise surge in revenue.

That will contrast sharply with next week’s Bank of Canada decision, when officials are expected to make the first 50-basis-point hike to the policy interest rate since 2000 as they work to bring consumer price gains down from a three-decade-high.

By the time Freeland publishes her 2023 fiscal plan in a year’s time, markets and economists anticipate the central bank will have raised borrowing costs by nearly 3 percentage points -- one of the most aggressive hiking cycles in decades.

“The budget is likely to add more conviction to our outlook that monetary policy will need to shoulder the brunt of reining in inflation,” Rebekah Young, Scotiabank’s head of fiscal economics, said in a report to investors.

Young pegs potential new spending through 2027 at about $140 billion to incorporate both Liberal election promises and costs of programs associated with a power-sharing deal Trudeau struck with the left-leaning New Democratic Party. That will be only partly offset by revenue windfalls from inflation and rising oil prices, as well as some new taxes, that Scotiabank predicts will generate $100 billion in income.

It’s possible, however, the government shows more restraint by rolling out new programs slowly or financing new measures with money reallocated from other programs.

“I can see them take a more prudent approach that is consistent with the supply-shock inflationary environment that we are in,” Kevin Page, chief executive of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, said by phone. That could include “reallocations to hold the spending line and a commitment to policy review of existing programs.”

Freeland will also try to cast new spending as growth-enhancing, which would make it easier to justify in an economy that’s right up against capacity. Otherwise, economists will argue the deficits will simply translate into higher interest rates -- making the nation’s indebted households pay a price for expansionary government policy.

Not that economists have any immediate worries about Canada’s fiscal position.

The base-case outlook is for strong growth in the foreseeable future that will allow the government to carry all the new debt. Corporate and household balance sheets are strong, and the nation’s commodity sector acts as a buffer to the headwinds from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has lifted prices for everything from oil to fertilizer.

The labor market is hot and businesses are showing signs they are beginning to invest again. Inflation helps, rather than hurts, government finances.

But the economic risks are beginning to tilt to the downside and Canada is much more vulnerable to a future crisis, with the possibility of stagflation looming.

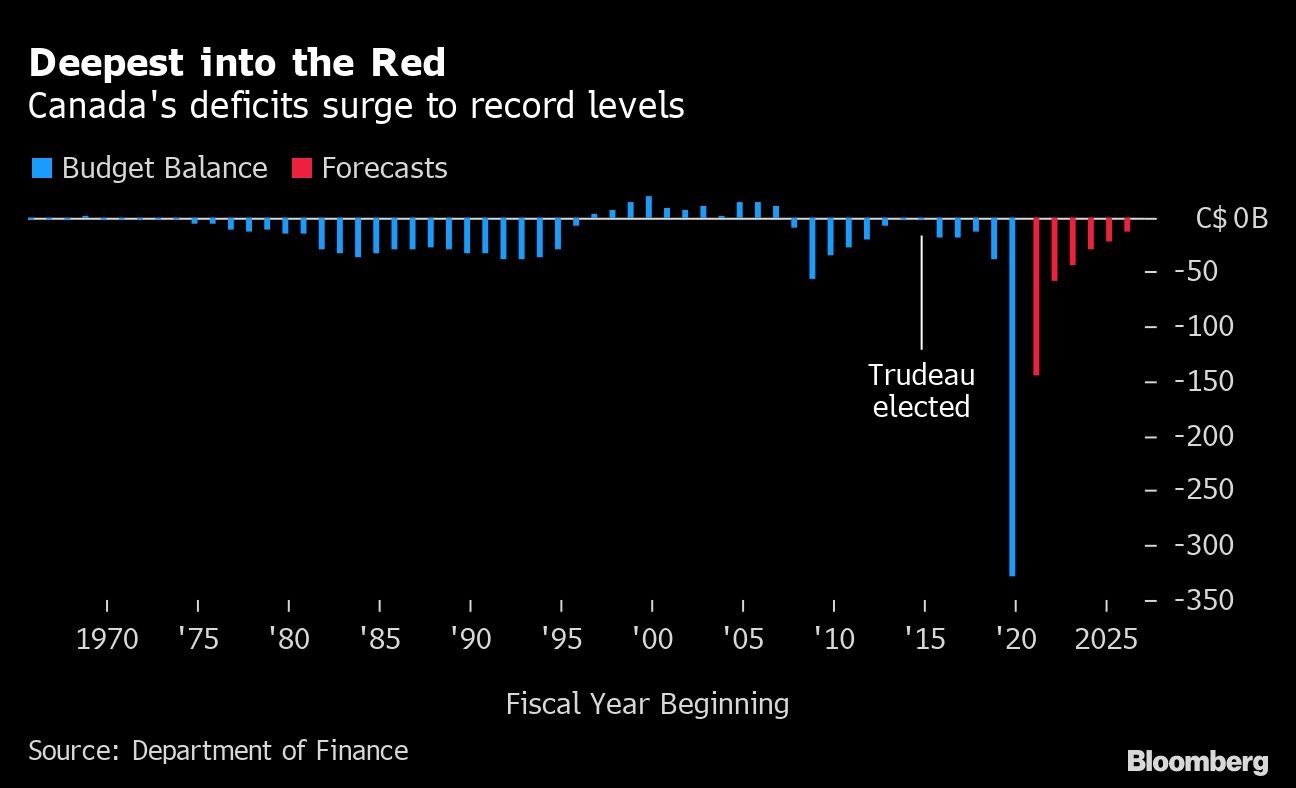

Debt has doubled under Trudeau, while spending is moving from transitory, one-off measures meant to counter the COVID-19 pandemic to new permanent social programs like child care and dental care.

There are also medium and long-term risks that have yet to be accounted for, including wartime pressure to ramp up defense spending and demands by provinces for more health-care funding.

All of this will eventually take the federal government beyond what is sustainable without eventually raising taxes or reducing existing spending.

“Freeland needs to start leading an adult conversation with Canadians about government priorities,” Chris Ragan, director of the public policy school at McGill University in Montreal, said by phone. “No one is talking about how to get the fiscal framework back in shape in preparation for the next big thing that hits us. As the last six weeks have demonstrated, there is always something serious coming at us around the corner.”

Piling on more deficits, meanwhile, threatens further erosion of the government’s credibility. Trudeau’s inability to stick to promised deficit trajectories or budget rules -- sometimes referred to as fiscal anchors -- predates Freeland taking the reins as finance minister in August 2020.

Yet, the government is again struggling to stick to commitments. Only four months ago, Freeland pledged to take “joint responsibility” for keeping inflation at its 2 per cent target when she renewed the Bank of Canada’s mandate for another five years.

Last year, the finance minister budgeted $100 billion in additional stimulus over three years in order to spur growth, but pledged to tie the spending to slack in the labor market. Now that the economy is at full employment, the government appears unwilling to pare it back.

On Thursday, the government will recommit to at least one budget target: keeping the nation’s debt as a share of gross domestic product on a downward trajectory.

Debt-to-GDP anchors in times of fast rising prices, however, provide little discipline. They could even be counterproductive by giving governments license to spend into inflationary conditions.

“There is definitely a fiscal reckoning coming and you have to adjust expectations of what is possible,” Page said.