Jul 21, 2022

ECB rushes to tighten as half-point hike matched by crisis tool

, Bloomberg News

ECB, BOJ Decisions Likely to Strengthen Dollar Further: Barclays

The European Central Bank raised its key interest rate by 50 basis points, the first increase in 11 years and the biggest since 2000 as it confronts surging inflation even as recession risks mount.

With Italy enduring a fresh bout of political turmoil, President Christine Lagarde and colleagues also unveiled a tool they hope will ensure markets don’t push up borrowing costs too aggressively in vulnerable economies, as happened in 2012 when the euro’s very existence was questioned.

“Price pressures are spreading across more and more sectors,” worsened by a weakening euro, Lagarde told reporters in Frankfurt. “Most measures of underlying inflation have risen further. We expect inflation to remain undesirably high for some time.”

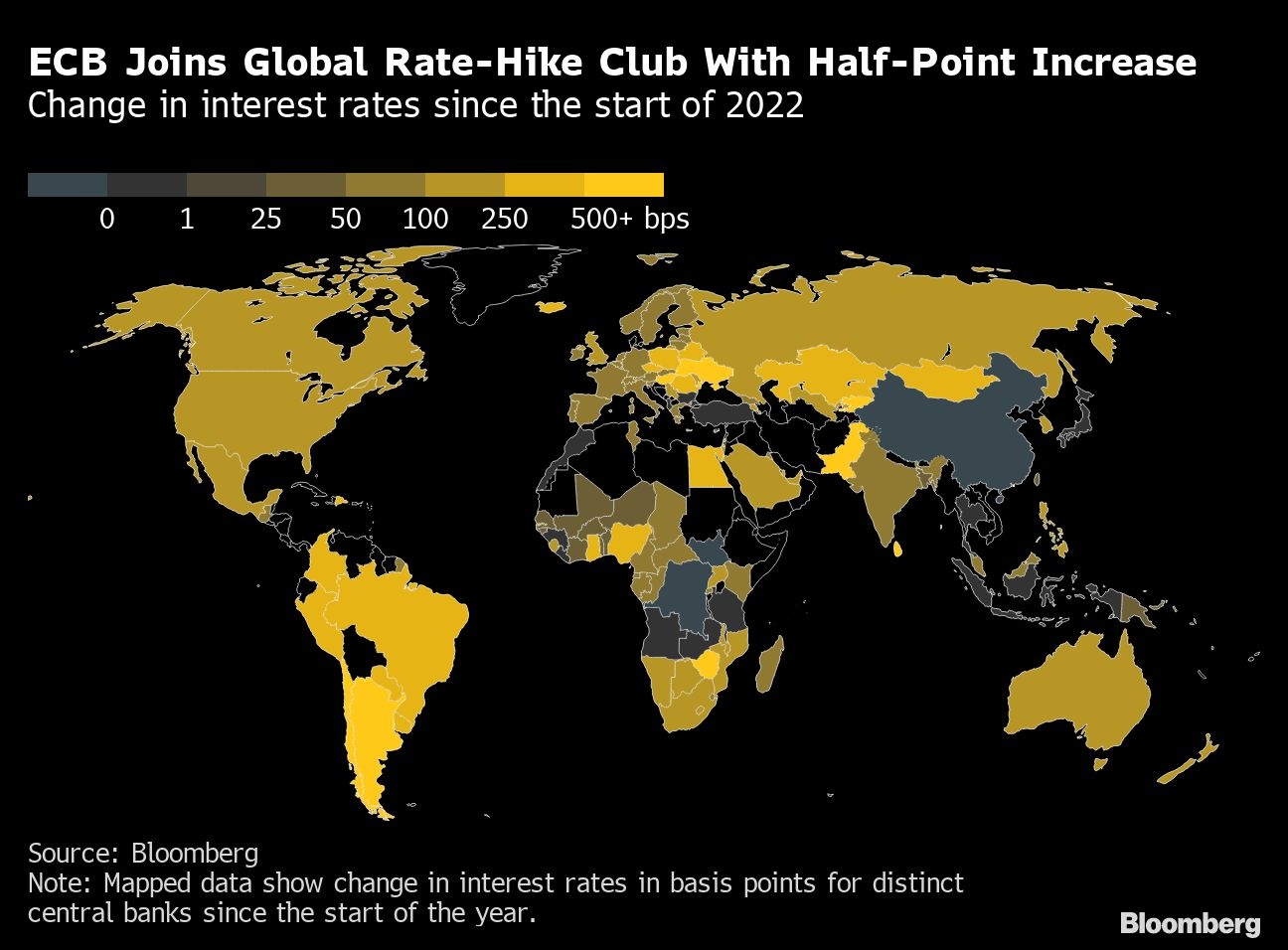

Thursday’s rate move aligns the ECB with a global push to tighten and ends an eight-year experiment with subzero borrowing costs. The ECB said in a statement that further normalization of interest rates will be appropriate at upcoming meetings -- prompting traders to step up wagers on the pace of tightening.

“The frontloading today of the exit from negative interest rates allows the Governing Council to make a transition to a meeting-by-meeting approach to interest-rate decisions,” it said, refraining from guidance on the size of future hikes.

As those steps are implemented, it said it will establish the Transmission Protection Instrument, which “can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics.” Purchases aren’t restricted “ex ante.”

Expanding on the tool, Lagarde said:

- All euro-area members are eligible

- The Governing Council alone will decide whether the TPI is used, taking into account “multiple indicators” including compliance with European Union fiscal rules

- TPI “will avoid interference with the appropriate monetary-policy stance,” suggesting bond purchases will be offset

- Some country-specific risks can still be addressed by an older instrument, Outright Monetary Transactions

- The Governing Council would “rather not use” TPI but won’t hesitate to do so if required

Thursday’s hike in the deposit rate to 0 per cent was twice the amount telegraphed until just days ago and was predicted by only four of 53 economists surveyed by Bloomberg. Lagarde signaled a 25 basis-point shift for weeks, before officials familiar with the talks said Tuesday that an increase of double that would be debated.

While a bigger move was agreed on, a small number of ECB officials initially favored a quarter-point, according to people familiar with the situation.

The ECB joins 80 international peers, including the US Federal Reserve, in lifting rates this year to fight red-hot inflation after months of predicting such pressures would fade. Consumer prices in the euro area are now rising by more than four times its 2 per cent target.

The central bank faces a tougher task than most. On top of setting monetary policy for 19 economies, the threat of a recession is greater as the war in neighboring Ukraine pushes up food and fuel costs, while a rising dollar leaves the euro flirting with parity. When the ECB last raised rates, in 2008 and 2011, it soon turned back as growth slumped.

Germany, Europe’s largest economy, is particularly at risk due to a greater reliance than most on natural gas from Russia, which has limited supplies in response to Western sanctions over its invasion. Flows through the Nord Stream pipeline resumed on Thursday after maintenance, bringing some relief to markets.

But as that happened, euro-area political risks came to the fore with the resignation of Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, Lagarde’s predecessor.

Kicking off a cycle of increases with an outsized hike shows the Governing Council is acting on repeated pledges to set policy based on the incoming economic data.

Since it last met on rates in June, inflation has continued to outpace expectations. It’s now headed toward 10 per cent and officials face a struggle to bring it back to the target over the medium term.

Banks will welcome the move to exit negative rates as it will boost their profitability. The only remaining countries with subzero policy are Japan, Switzerland and Denmark.