May 22, 2018

North Korean Restaurants in Cambodia Stay Open Despite Sanctions

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Three North Korean restaurants are operating in Cambodia’s capital in apparent violation of United Nations sanctions that took effect earlier this year.

The restaurants in Phnom Penh, which all have names including the word Pyongyang, the capital of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, are staffed by North Korean workers and offer products from that country, including blueberry wine and ginseng. They’re part of a well-documented global network of businesses that have been generating cash for the North Korean regime for years.

New sanctions adopted by the UN Security Council in September in response to North Korea’s testing of nuclear weapons required that such businesses be closed by Jan. 9. The resolution banned “the operation of all joint ventures or cooperative entities, new and existing, with DPRK entities or individuals, whether or not acting for or on behalf of the DPRK.”

William Newcomb, a fellow at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies in Washington and a former member of a UN Security Council panel of experts on North Korea sanctions, said “DPRK restaurants operating abroad with DPRK staff are at least cooperative entities, if not set up as joint ventures, and are prohibited.”

U.S. President Donald Trump is aiming to get countries to comply with tighter sanctions to put pressure on North Korea, even as Kim Jong Un reaches out for talks about his country’s nuclear program. The two leaders are scheduled to meet in Singapore June 12, though Trump cast doubt on Tuesday about whether the summit will take place then.

Khieu Kanharith, Cambodia’s minister of information, said his country complies with UN regulations and referred further questions to the foreign ministry. A spokesman there didn’t respond to emails and phone calls. Faxes sent to the North Korean embassy in Phnom Penh didn’t go through, and a phone number listed in online directories connected to a man who identified himself as a farmer and said he has had the number for three years and continues to get calls for the embassy.

Name Tags

All three restaurants in Phnom Penh feature waitresses wearing name tags in the red and blue colors of North Korea’s flag with their names written in white in place of the star. The women have similar shoes and hair styles, and they sing songs, play music and dance as well as serve food.

At the Pyongyang Traditional Restaurant, in a neighborhood filled with embassies, about a dozen waitresses served dishes including bibimbap and cold buckwheat noodles one evening last week to a room filled with Mandarin-speaking businessmen, a group of South Koreans and a few European tourists. North Korean products and magazines were for sale on a shelf near the entrance.

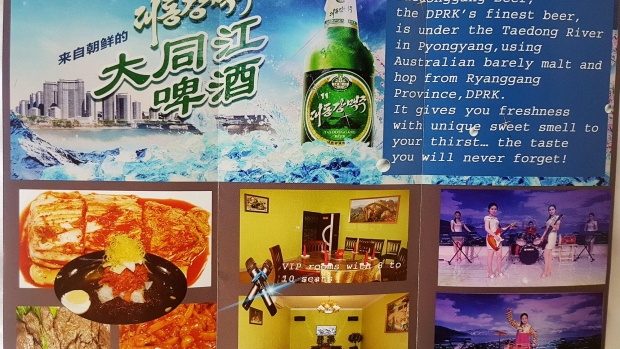

Another restaurant, Pyongyang Unhasu, is in the northwestern part of the city next to a Carl’s Jr., a U.S. fast-food chain. It has bright yellow tablecloths and seating for 200. Young women stand outside greeting customers. Brochures available inside advertise North Korean beer and wine made with blueberries from the Paektu forest.

The third restaurant, Pyongyang Arirang, is on a busy street around the corner from several government ministries.

Employees who answered the phones at the three restaurants on Tuesday said they use and sell products sourced from North Korea. A woman at Pyongyang Arirang said her establishment was staffed by North Korean as well as local workers. A man at Pyongyang Unhasu said he was North Korean but wouldn’t comment about other employees. A waitress at Pyongyang Traditional said she couldn’t talk about the nationality of the restaurant’s workers. All three declined to say anything about where the money went.

“I’m mortified by your question,” Ri Chol Nam at Pyongyang Unhasu said when asked about the restaurant’s finances. “I can’t answer that.”

Cash Only

The cash-only Pyongyang restaurants are part of a network that at its peak had more than 100 outlets across China, Southeast Asia, Russia and Eastern Europe, according to Kim Byung-Yeon, an economics professor at Seoul National University who researches North Korea’s sources of financing. The Phnom Penh Post reported that eight such restaurants were operating in Cambodia as of 2015.

“All of these restaurants abroad are operated with one of the state institutions -- it could be the party, the army, the cabinet or a local government,” Kim said. “All the people are selected on the basis of age, beauty, how they sing songs. They do not have to be a party member, but they have to make money for the institution.”

As many as 60,000 North Koreans are working in more than 50 countries, according to estimates by South Korea’s foreign ministry.

‘Special Relationship’

Cambodia and North Korea long had what government officials in the past have termed a “special relationship.” Norodom Sihanouk, the former king of Cambodia, considered Kim Il Sung, founder of North Korea and the current leader’s grandfather, a close friend. Sihanouk had a residence in Pyongyang and would fly back and forth to Phnom Penh on an Air Koryo jet accompanied by North Korean bodyguards. U.S. diplomats in Cambodia in the 1990s said the plane would bring in counterfeit U.S. dollars called supernotes and return to North Korea with goods and real cash to support the regime.

These days it’s much harder to get the money that the Pyongyang restaurants generate back to North Korea, Kim said. Chinese banks, too, are subject to UN sanction orders to halt money transfers and close any accounts being used to support the government there.

“Revenue generated from North Korean restaurants and overseas workers is sent back to the Kim regime,” where it may be used for nuclear weapons and missile programs, said Anthony Ruggiero, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington and a former official of the U.S. State and Treasury departments who investigated the illicit financing of North Korea. “UN sanctions require countries to freeze assets and resources that support the weapons programs.”

The sanctions also require that North Koreans working abroad be repatriated “immediately but no later than” December 2019.

Despite the tightening of sanctions, implementation has continued to be an issue. At a briefing for the Security Council in February, Dutch diplomat Karel Jan Gustaaf van Oosterom said “a large number” of countries hadn’t submitted required reports on enforcement.

--With assistance from Peter Pae and Jihye Lee.

To contact the reporter on this story: Sheridan Prasso in Hong Kong at sprasso@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Robert Friedman at rfriedman5@bloomberg.net, Daniel Ten Kate

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.